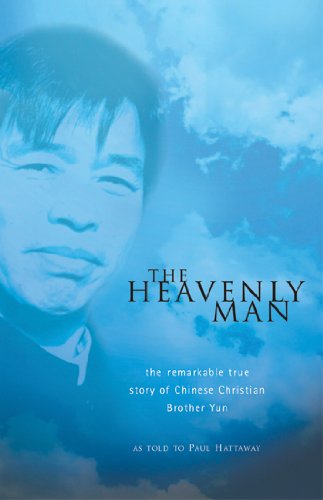

G. Wright Doyle Ph.D., Sarah E. Cozart, Review of: The Heavenly Man. Brother Yun with Paul Hattaway. Carlisle, UK: Piquant, 2003.

This story of the life of Chinese house church leader Brother Yun is an amazing testament to the power of God in the face of persecution. The accounts of the suffering Brother Yun has faced in only the last few decades are shocking. One expects to read about such things in relation to Russia under Stalin or the first-century Christians, but not in modern-day China. To the complacent Western reader, the knowledge that this kind of Christian courage and faith exists today is both inspiring and humbling. Brother Yun’s growth in knowledge and understanding of the Lord shows both his great faith and his deep humanity. He struggles with spending enough time with his family, becoming so caught up in the work of God that he forgets his intimate relationship with Him, and finding out what God’s will is for him in the various stages of his life – freedom, imprisonment, travel.

The first miracle that Brother Yun recounts—that of receiving a rare Bible exactly as he envisioned he would—shows the powerful ways in which God works in situations where people have absolutely nothing. He delights in showing His power through our need. The Lord also healed Yun’s father of cancer in 1974, which led his entire family to faith in Christ. When Yun was imprisoned in 1984, by the Lord’s power he neither ate nor drank for over two months, becoming weak and emaciated but, miraculously, not dying. This fast became a powerful testimony to the other prisoners of the Lord’s work in Yun’s life, and several prisoners who had mocked and mistreated Yun came to know God through his example. This happened every time Yun was in prison. The other prisoners would often disdain him for his lack of resistance to mistreatment, but would then desire whatever Yun had that they obviously did not. Many men were led to the Lord in this way.

The book also includes many responses by Yun’s wife, Deling, to the events he describes. The perspective that she offers is valuable and interesting. Deling obviously struggled with all the difficulties her husband and family faced on an almost daily basis, but her undying faith and trust in God enabled her to stand beside Yun during even the most trying of times. Her story shows, however, how hard it can be for great Christian leaders such as Yun to balance time between ministry and family. Yun realizes this eventually and pledges to see to his family first and his other ministry second.

The Heavenly Man follows Brother Yun from the beginning of his life and his conversion to his release from prison in 2001. Various aspects of his ministry are discussed, with special attention given to his times in prison and his efforts to unify the house church movement in China. The gripping story, though graphically violent at times (in the descriptions of the tortures Yun received in prison), instills in the reader a desire for faith like Yun’s, and for the opportunity to work on the ‘front lines’ of Christianity the way Yun has. It is, along with Bold As A Lamb (about pastor Samuel Lamb), highly recommended to any Christian, but especially to those interested in China.

-Sarah Cozart

In talking with a Chinese sister who has known Brother Yun for many years, I learned a few things that remind us that no one, not even such great Christian leaders as this one, is immune to temptation. For example, the perceptive reader will notice that the house churches led by Yun and his older mentor Peter Xu resemble the Roman Catholic Church in their rigid authoritarian structure. Millennia of imperial governments have not taught Chinese any other style of leadership.

Such absolute power will inevitably lead to factions; resentment, and then rebellion, from below; and even allegations of corruption, including financial and sexual. Yun has not been charged with misconduct, but other top leaders mentioned in his narrative have, and there seems to be less harmony among the groups than he depicts.

This sister, who has extensive knowledge of the house church movement, also questions whether Yun and other leaders should be outside of China; she claims that they could operate from within. Others have voiced questions about some aspect of the Back to Jerusalem movement, including the solicitation of foreign funds.

Finally, an outsider would not be able to know that all the testimonials of the veracity of Yun’s story come from his close friends and associates. While this might lend greater credibility to his account, it has caused some to question the objectivity of the endorsements.

Nevertheless, no one questions whether Yun suffered greatly for his faith, demonstrated heroic zeal in spreading the Gospel, experienced many miracles, and evinces a love for God and His Word that should lead us all to our knees.

One of Yun’s most noteworthy actions was to refuse to give information to his prosecutors or to engage in unnecessary dialogue with them. Perhaps he had in mind the mistakes made by Wang Mingdao a generation earlier, when subtle political arguments temporarily misled that great man and induced him to write a self-criticism. Wang admits that fear also played a part in that defeat (which he later redeemed by refusing to join the Three Self Movement and willingly went to jail again). Yun’s steadfast courage enabled him to resist all such temptations.

The Heavenly Man illustrates the overall picture of Christianity under Communism as portrayed in Adeney’s China: The Church’s Long March; Lambert’s The Resurrection of the Chinese Church and China’s Christian Millions; and Aikman’s Jesus In Beijing.

-Wright Doyle